Baggio…oh yes…oh yes…oh yes!!! What a goal by Baggio! That’s the goal they’ve all been waiting for!

The ‘they’, the excitable ITV commentator was referring to, was the whole of Italy during World Cup Italia ‘90, as an entire nation had waited impatiently in anticipation, then watched in expectation, as their latest ‘golden boy’ – a magical fantasista – made himself known to a global audience. Making his first start of the finals, and wearing the no.15 shirt, Roberto Baggio announced himself to the world, gracefully gliding through the Czechoslovakian team from the halfway line, before sending the goalkeeper the wrong way to score. Collapsing to the turf, for a brief moment, all the intense pressures of being world football’s ‘next big thing’ had been lifted; Roberto Baggio had arrived.

In truth, Baggio had ‘arrived’ much earlier. In Italy, he was already a star attraction in Serie A, where he had been lighting up the league for the previous few seasons in the city of Florence, with Fiorentina. His mercurial talent would remain a fixture in the Italian top-flight for the next 14 seasons (playing 18 in total). But for all those who witnessed his magic and the outstanding feats he achieved during this time, the extraordinary thing is, he played the majority of his career suffering with injury. You see, Baggio’s story was almost over before it had even begun.

One of eight children, Roberto Baggio was born in Caldogno in the north-east of Italy, near Vicenza. As a young boy he showed an early interest in football. When not using his parents’ bedroom as a makeshift pitch (where the goals consisted of a double bed and a wardrobe), he was outside, often disappearing until dusk playing with a ball, leaving his father to go searching for him on his bike. The youngster was soon scoring in real goals as his talent was spotted by village club, Caldogno, at just 9 years old. By the age of 11 he was on the radar of nearly every club in Italy, and was soon starting to be hailed as a prodigy after scoring 45 goals in just 26 games. After scoring 6 in one game, scout Antonio Mora took him to Vicenza who paid Caldogno just £300.

The step-up in level made no difference to the now 13 year old Baggio, who hit a whopping 110 goals in 120 youth-team games before being promoted to the first team, aged just 15. Now seeking to emulate his footballing idol – Brazilian fantasista, Zico – his form for Vicenza (then in Serie C-1) during only his third senior season, helped win promotion – but they would have to play in Serie B without their young star. Baggio’s stock had risen to such a level that two Serie A giants began chasing his signature, with Juventus confident of securing a deal. However, a last minute bid of around £1.5million from Fiorentina ensured they won the race.

What should have been a celebration soon turned to tragedy however as just two days before the deal was finalized, Baggio shattered the cruciate ligament in his right knee whilst playing against Rimini. Aged just 18, with the world at his feet, he was victim to a career-threatening injury and was told by doctors he would never play again.

There was cause for optimism however. Fiorentina chose to honour the deal and stood by their new signing, sending him to France for pioneering surgery – thus ensuring a strong bond between club and player that would be hard to break in the future. But these were the darkest days of Baggio’s life. Mentally, they helped define him as a person and gave him a great inner-strength and belief, but physically, the injury would remain with him for the rest of his playing career. His pure love for the game though, would simply not allow him to quit:

I underwent surgery that was very risky at the time. They had to drill through my kneecap and reattach all the ligaments with 220 internal stitches. I am allergic to the most powerful painkillers, so I was in absolute agony day and night for months afterwards – but I held on because of my passion for the game.

Baggio missed nearly all of the next two seasons through injury, and in truth he never fully recovered. Upon retirement he stated that if he were to play only when he didn’t feel pain, he would have stepped on the pitch “only two or three times a year”. The incredible will he showed to ‘never give up’ also came from a more surprising source during his recovery, which again marked him out as being different from the rest.

In a staunchly Catholic country, he converted to Buddhism. At just 21 years old he made the choice whilst in the eye of the public, joining the Soka Gakkia order which emphasizes the importance of self-motivation over blind obedience. Its teachings also encourage contribution to the well-being of friends, family, community and the promotion of peace, culture and education. Followers are devoted to ‘inner transformation that enables people to develop themselves and take responsibility for their lives.’ Baggio would eventually have one of the order’s mantras embroidered on his captain’s armband.

Once playing in the famous purple of Fiorentina, Baggio quickly became the fans idol and embarked on a happy couple of years. He made his debut against Sampdoria and scored his first goal against the champions elect, Napoli in 1987. He continued the next three seasons in superb fashion as his style of play delighted all who watched. Even for a fantasista, he scored at a rapid rate with almost a-goal-every-other-game ratio.

But it wasn’t the quantity of the goals which stood out – it was the quality and variety. Spectacular, and from all angles and areas, he’d score curlers, volleys, dribbles through the defence (including the keeper), free-kicks, penalties and one-on-ones – finishing was never a problem for Baggio. So natural and cool in front of goal, the Italian’s said he had ‘ice in his veins’. But it wasn’t just goals – as a fantasista he also created so much more. This led former Argentine and Viola midfielder Miguel Montuori to famously claim in the ’88-’89 season that Baggio was:

…more productive than Maradona. He is without doubt the best number 10 in the league.

A call-up to the Azzurri naturally followed, making his debut in 1988 versus Holland, and scoring his first international goal five months later during his first start against Uruguay with a trademark free-kick. At the end of that season he married his childhood sweetheart Andreina, and it was also during this period he was christened with one of the most famous nicknames in the game. Tying his already long hair at the back ‘Il Divin Codino’ was born – the divine ponytail.

Firing Fiorentina to the UEFA Cup final but narrowly losing to Juventus, Baggio was now a huge star in Italy and the rest of Europe was taking note. To the disbelief of the Viola faithful however he was sold, against his will, for a world record transfer fee to Juventus, just prior to the 1990 World Cup finals. The record £8 million move sparked three days worth of riots in the city of Florence, such was the fans disappointment of selling their idol to a hated rival. The ‘match of poison’ would now take on even greater significance. Roberto was preparing for the finals with the Azzurri at Coverciano but was sickened by the violence, and left feeling betrayed by the club’s stance to portray him as the villain in seeking the move.

Baggio would ensure the truth was known at the next meeting between the two clubs however, as the Italian saying goes: Sempre nel mio cuore – you’ll always be in my heart. Proving this to the Fiorentina fans, he refused to take a penalty for Juventus against them (he was the designated taker), which Juve duly missed. He was then substituted but left the pitch at the Artemio Franchi stadium clutching a thrown Viola scarf.

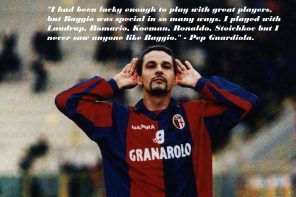

After his world record move, Baggio had an initial frosty relationship with the Juventus faithful – the penalty incident in Florence hadn’t exactly endeared him to his new public. However his sensational abilities soon won them over. During his five seasons in Turin Baggio was confirmed to be what many already knew – he was the greatest player on the planet and thus became a global superstar, destined for legendary status. In 1993 he was voted World and European Player of the Year after leading Juventus to UEFA Cup glory (his first major trophy) and in 1995 he finally won the Serie A title (alongside a Coppa Italia).

Such was his play – in conjuring fantasy on a football pitch at a time of ever growing athleticism and dour tactics – fans around the globe adored him. He was the reference point to everything still magical in the game, a reminder to when skill ruled over physicality. A perfect example of the number 10 shirt; a symbol for the fantasista.

The angels sing in his legs,

former Fiorentina boss Aldo Agroppi famously said, such was his beautiful style of play.

The emergence of Alessandro Del Piero, alongside the ‘tactical differences’ coach Marcelo Lippi wanted to implement, led to the sale of Baggio to AC Milan.

Although he won his second Serie A title here, he was never fully appreciated – again suffering with injuries, and against the coaches who preferred the more athletic, over natural skill. The number 18 shirt on his back looking as alien as the great fantasista himself sitting on the bench. His frustration growing at the way football was losing its artistry, Baggio stated:

It’s better to have 10 disorganised people who can play football than 10 organised people who just run.

Disillusioned by the big clubs, Roby chose mediocre Bologna to showcase his talents next. Feeling ‘born again’, complete with a closely shaven head and unshackled from the tactical leash, he was given free reign and promptly had his best scoring season in Serie A, hitting the net 22 times in just 30 matches. Such was his form, a recall to the national team for the 1998 World Cup was preceded by one last ‘big’ move to Inter. Initially things looked promising at his second spell in Milan. However once again injuries, along with the return of coaching nemesis Marcelo Lippi, ensured Baggio had another miserable time. After refusing to be ‘a spy in the dressing room’ for Lippi, the coach tried to ‘destroy’ him. Baggio wrote in his autobiography:

The Lippi I had at Inter declared war on me. The problem was that even when I didn’t play, I was always on people’s lips whereas Lippi, try as he might, just couldn’t make people like him. He wanted to destroy me, but he didn’t succeed.

Baggio recounted an example of the coaches animosity towards him during a training session:

I played a 40-yard pass to free Bobo Vieri, who scored. He turned round and applauded me, so did Panucci. It was a normal thing between team-mates but Lippi went crazy. ‘Vieri, Panucci, what the fuck do you think you’re doing? Do you think this is the theatre? We’re not here to clap each other!’

Roby left Inter with his head held high however and with some positive memories. He scored two late goals to beat Real Madrid in the Champions League, and in his final appearance versus Parma – a Champions League qualification playoff – he scored two wonder strikes to ensure victory and progression for the club.

Many thought the final chapter in the Baggio story had been written when he chose little Brescia as his final destination. In realizing their coup of capturing an historic great, coach Carlo Mazzone set about building a team around the mercurial number 10. However, yet another early injury kept Baggio for months. On his return, Brescia were at the foot of the table – but not for long.

Inspiring his team, Roby fired in 10 goals (not to mention many assists) in an incredible end of season run which saw Brescia finish 7th in Serie A and qualify for the Intertoto Cup. For the next three seasons Baggio enjoyed some of the best form of his career, scoring many wonder-strikes and creating with the vision only a true great can see. Every season Baggio played, Brescia remained in Serie A – something that had rarely happened to the provincial club (indeed, the season after his retirement they were relegated),

And so it came, on the 16th May 2004 at the San Siro, Roberto Baggio played his last ever game versus former club, AC Milan. The capacity crowd, knowing the significance of the event, had come in their droves to bid a fond farewell to a player who transcended club loyalties. With banners dedicated to him in every corner of the stadium, both home and away fans chanted his name constantly whilst applauding his every touch. With 84 minutes played, the number 10 was held aloft. As he walked off the pitch he was given one of the warmest standing ovations from the crowd, any player had ever received. Teary-eyed, he applauded back, and was embraced with heartwarming affection by the opposition captain; friend and former team-mate Paolo Maldini. As he disappeared down the tunnel, the world of football had just witnessed the last of the true fantasista.

Baggio’s playing career was full of contradictions; he was a paradox. A character which such strong beliefs and confidence, yet there remained a fragility to him. For all the immense talent which would mark him down as one of the greatest in the history of the game, he always seemed to be fighting against an ‘enemy’ – whether that would be injuries, coaches or just fate, his fragility only served to endear him to the public as he battled the odds whilst remaining true to the spirit of the number 10 shirt. He approached everything with great humility despite his fame and stature, and his humble, friendly manner ensured he was also much-loved by fellow professionals and team-mates throughout his career. This is a player who auctioned off his winning Ballon d’Or to give proceeds to the victims of a flooding disaster, who campaigns for humanitarian aid and vowed to fight world hunger and disease stating it “a moral obligation”.

His exploits for the national team, spanning three World Cup Finals (scoring in all – the only Italian ever to do this) also contributed to Baggio’s popularity around the globe. From scoring that goal in Italia’90, he almost single-handedly dragged an average Italian side to the final in USA’94, scoring five goals (all in the knockout stages) before missing that penalty, for which he is most unfairly remembered – despite both Franco Baresi and Danielle Massaro already missing during the shoot-out, and despite playing half-fit after suffering injury during the semi-final victory. He later admitted:

Even if I’d have had to play with one leg [in the Final], I would have done.

Somewhat banishing that penalty ghost, he scored a decisive spot-kick during France’98 to give Italy a late equaliser against Chile, as well as scoring in the shoot-out versus hosts and eventual champions, France. All in all, Il Divin Codino played 16 times in World Cup Finals, scoring 9 times (a joint record), and was only ever eliminated from the competition via penalty shoot-outs – finishing third, and as a runner-up in two of those tournaments. Capped by the Azzurri only 56 times whilst scoring 27 goals, his infamous penalty miss came at a time when he was at the peak of his powers. The unfair blame placed in his shoulders initially, by then coach Arrigo Sacchi led to many years left out in the wilderness. Just as the big clubs had done, the national team never truly appreciated his talents, especially post ’94.

One Italian best summed up the treatment of their most gifted ever player, when he wrote this upon his retirement:

Italy loved you, Baggino, but it also obscured and humiliated you.

Technically perfect, his penalties, free-kicks, vision, skilful dribbling and consistency in front of goal made him a player easy to adore. He never enjoyed the success his talents deserved at club or international level but in ability, creativity and fantasy alone, Baggio deserves his place amongst the all-time greats. Many footballers may have bigger trophy cabinets, but very few have been adored as many, worldwide. In FIFA’s global internet poll in 2000 to choose the greatest player of the 20th century, Baggio came 4th behind Maradona, Pele and Eusebio.

In Serie A alone his goalscoring exploits were phenomenal. One of only six men to score over 200 goals in the league, he finished up with a total of 205 goals from 452 games – not bad for a non-striker. More outstanding though, is that an incredible 96 of those goals were decisive for his teams – meaning they were either equalizers or winners.

Scoring over 300 career goals in all competitions, it wasn’t just the quantity, but the quality of strikes – some of the most beautiful ever seen, scored on the domestic, European and International stage. They will live long in the memory of football fans around the world.

These incredible feats and magical memories were provided by a true great. How many other so called ‘greats’ had to fight against so many obstacles throughout their careers, being written off unfairly before consistently proving the doubters wrong and providing inspiration to others? A player that by rights, could have retired in 1985 due to his horrific injury, but instead chose to suffer the pain throughout his glittering career, all for the love of the game.

All that’s left to say is ‘Grazie Roby’, the finest fantasista of them all!

Vital Stats

- Born: 18th February 1967 in Caldogno (Italy)

- Height: 1.74m / 5ft 7”

Club Career

- 1982-1985: Vicenza – 36 apps / 13 goals

- 1985-1990: Fiorentina – 94 apps / 39 goals

- 1990-1995: Juventus – 141 apps / 78 goals

- 1995-1997: AC Milan – 51 apps / 12 goals

- 1997-1998: Bologna – 30 apps / 22 goals

- 1998-2000: Inter – 41 apps / 9 goals

- 2000-2004: Brescia – 95 apps / 45 goals

- Totals: 488 app / 218 goals

International

- 1988-1999*: Italy – 56 caps / 27 goals

* was called up in 2004 to play a friendly v Spain before his retirement in honour and recognition of his services to the national team.

Honours

- World Player of the Year: 1993

- Ballon d’Or: 1993

- UEFA Cup: 1993

- Serie A Champion: 1995, 1996

- Coppa Italia: 1995

To paraphrase Baggio himself (in an Italian interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7FbNhFuxiYw):

“The Fantasista (creative playmaker, mezzapunta, il fuori classe, number 10, the Renaissance artist) is the one who does what they all don’t do… Someone who does [singular] amazing things… [That instant], that passion, that approach, [that presence], [that courage]… The playmaker should have [reflexes] more than others, for sure, as dictated by the speed of his reasoning… [graced with] such visionary understanding of what is unfolding in that action, including the move of a partner in advance, and [the geometry of the game in an instant]… [The rest is] to be guided by pure instinct – and this requires absolute freedom.”

It goes without saying, the Fantasista – the permanent-class, creative-imaginative, free-role playmaker – is quite extinct in today’s football, where at most we see some talent, power, and speed, but not GENIUS – and at worst over-hype machination, baseness, and mediocrity. Watching overly commercialized, overly plasticized football today (despite it’s a true joy to see Messi play personally) is a stupendous mundane redundancy and luxury of life I cannot tolerate. Musicality is banished and the song is banal – so the sport is just mere sporting activity and a commercial plague, not a transcendental joy, not art, not semantics.

Other than in history, the IDEA (Eidos) of Genius, like pure moments, still lives in the Universe and Baggio, as per the infinitesimal Monad and Geometry that he is, is the greatest Italian embodiment of it, an ontological category greater than Meazza, Rivera, Mazzola, Boniperti, Antognoni, Platini, Totti, Del Piero (in the silhouette of Pele, Maradona, and Zico, yet still more intrinsically beautiful and more tragic than them): his vision is singular and sovereign, his first-touch sacramental and alien, his dribbling is the zenith and geometrical stuff of Renaissance painters (Caravaggio, Raffaelo, Michelangelo, Leonardo indeed) as are his curling shots and other perfectly carved moments of curvature, rapture, and infinite self-measure , his entire soul and presence only a poet and painter can describe (plus all the paradoxes, all the sacrificial tragedies and ironies: having deeply broken his knee and the magical foot twice very early in his Vicenza and Fiorentina days, thus admittedly he never ever played with even 60% fitness that the game demanded, not to mention his visionary clashes with pervasive tactical mediocrity) – as only pure geometry and philosophy can be ascribed to it. And, like all Platonic ideals, profundity demands tragedy (and other Messianic traits) without reserve – to unbelievable lengths.

Il Grande Baggio! Il Grande Artista! Il Divino Codino! Il Genio Assoluto! M-A-E-S-T-R-O.

This is a very fine tribute to the singular poet and painter of Renaissance genius, the contrapuntal and tragic musical creator, the meaning and quotient of true art, the “Dying Swan” ballerina of football, “il grande fantasista” – Roberto Baggio. There is talent, and there is Genius – so very few know the categorical difference. And Baggio is Genius, not talent – and it almost makes no sense that there is actually an artist in the football field. When that is the case, joy is infinite and wonderment has no residue.

Just as there is IDEA (Eidos), which is absolute, and there is mere thought or opinion. Baggio is “IDEA sine qua non”.

The absolute difference is like that between the tragic and creative Mozart of isolated Salzburg (who withstood poverty in his creative adult years and whose fame was largely posthumous) and the “happy and successful” Salieri of the court of Vienna. All this has nothing to do with fame and certain cumulative trends. In the Renaissance, Baggio could have lived a single life time of solitude, creativity, and originality – of artistic creation and philosophical ideation, of suffering, alienation, and hence understanding just like some other geniuses undiscovered at large during their often short (or painfully long and lonesome) lifetimes – and his fame could have only been posthumous. Either way, he would have created what only he could and must create.

Baggio has more intrinsic beauty than even Maradona (who is no doubt the best overall) and Zico (not Pele, since Pele, while truly phenomenal, is not comparable in this category of beauty as IDEA), the only ones comparable to him in singularity, not mere contingency and accolades. Who else dare proclaim it with epistemic, essential understanding (and not just acquired, accidental, contingent knowledge, including all the panhandling of statistics and history), as Gianni Brera once did? Brera saw the likes of Meazza, Mazzola, Rivera, Antognoni, Platini, Maradona, Zico play in the Serie A — and Baggio was his purest joy, truth, and discovery.

As of today, among recent footballers, Del Piero – who idolized Platini as well in his youth, who succeeded Baggio to the number 10 of the beautiful game, and who said, “No one should dare to say I snatched Baggio’s place at Juventus” – and Pirlo can genuinely reflect on Baggio endlessly with great passion and fondness. Just ask them of Baggio and Baggio only, not even of “football”. Baggio is a universal individual (universal quality), while football is a global phenomenon (global property).

Just look at this Baggio composition highlighting his “sum total” of his beautiful dribbling, vision, and goal scoring during Juventus’ match against Lazio: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgRv6c6v68M&spfreload=10

Such a piece of isolated footage of the fantasista, Roberto Baggio, il Divino Codino (the Divine Ponytail)! A passionate friend (Guti) says there, “Roberto Baggio (Caldogno, 1967) fantasista e seconda punta in possesso di grandissima geometria e di eccezionali doti tecniche, è considerato uno dei migliori calciatori italiani di sempre.”

To me, Baggio is like Da Vinci reincarnated in the pitch. He is one of the few spectacular geniuses whose intoxicating charm and splendor comes from beyond the earthly confines. Baggio, Prince of Solitude, is single-handedly able to transform the geometry of the game because he himself is the soul of the game. It’s not just football. Watching Baggio play is a form of worship for those who know the essence of true art.

Robi is a rare kind of beauty, a beauty that encompasses all the joy and sorrow of genius. He is Pure Class, a pure fantasista, a genuine number 10. Technically, he, nicknamed Caravaggio, belongs to the renaissance class of Maradona and Zico only. Intrinsically, he has more class than Platini.

Watch his dignity, charm, and magic especially at Juventus. His dribbling skills, finishing touches, and subtly curved free kicks remain unmatched today not only in Italy but in Europe. Antonio Conte once said of him, “He is able to dribble past 11 players and score.” In reality, what he does with the ball is paint the field with curves of infinite passion and tenderness.

His greatness, his legend, is not built upon collective glories, but upon singular passion and sheer beauty. He need not win trophies, for Baggio is Baggio, pure and lone truth and idea – a beauty that is a pure satisfaction unto itself.

I’ll say it again and again:

Roberto Baggio is the singular geometry of the beautiful game, its perfect IDEA, its quintessential sense, space, time, soul, its living mastery, creativity, vision, presence.

Again, Gianni Brera – who saw Meazza, Rivera, Mazzola, and Boniperti play – implied that Baggio was the purest thing of truth, flair, beauty – a true fantasista, maestro, the last classic number 10 – he’d ever seen, in terms of pure IDEA (Eidos, Logos, Kudos, Quality), not just mere collective accolades and such contingencies. Baggio broke his knees so young and endured too many devastating surgeries on them, yet the pure genius that he was still shone from the depths of hell and alienation. The elderly Agnelli coined the ecstatic Renaissance terms Rafaelo, Caravaggio, and Pituricchio for FIRST Baggio and then Del Piero. Del Piero and Pirlo thought the same, regarding Baggio as their ultimate teacher. A true knower, who KNOWS the first principles of what constitutes the rare singular ARTISTS that Maradona, Zico, Baggio are, should have more breadth and depth of knowledge of football history and even original concepts of ART and artists, not just stats and its too easy regurgitation.

Baggio is the internal logic of semantics and syntax in footballing art, which is beyond mere collective contingencies. Know (or never know) first what QUALITY is as a singular truth, horizon, and category in logic, then perhaps dare not to comment. True logic and taste are hidden at large in this world. Del Piero is great and more of an artist and artwork than Totti – Cassano comes close to the amount of pure talent. But Baggio – the Dying Swan Artist; again the soul, sense, space, and time or the entire singular GEOMETRY of the beautiful game – is categorically different still. Baggio has the absolute singularity and class, in the same Renaissance group of pure mastery, vision, and creativity of Zico, Platini, and Maradona, even above the likes of Meazza, Mazzola, Rivera, Boniperti, Boninsegna, Antognoni. Opinions, no matter how hyped up and popular can never equal a single IDEA. Idea – like Genius – is absolute by definition no matter how unpopular, difficult, and tragic, while opinion is relative. The narrow-minded ones too often “mix” and blur them arbitrarily and aggressively. Small fries with no conceptual (philosophical, if you like) originality in art, football, or anything in life interest me not whatsoever.

Only mindful comments like this one can begin to approach the true Nature of the Masterful Artist: “Roberto Baggio fantasista e seconda punta in possesso di grandissima geometria e di eccezionali doti tecniche, è considerato uno dei migliori calciatori italiani di sempre.”

Always go to read article abochhiut the “classic number 10” because of the rapid decline in today’s fòotball . I found it alarm that most messi/To fans regard messi has the greatesr player of all time just because of his scoring exploit. Today’s football does not concern itself with artisry , Grace which was the hallmark of the fantasista. All that interest today’s footballer is awards and money which is a shame to beautiful game that is getting more ugly everyday that passes..i

Craque! Craque! Craque!

Roberto Baggio is my hero!

Grazie di tutto Baggio!

The best players of all time were Roberto Baggio and Lothar Matthäus.

Grazie di tutto Baggio!

Danke für alles Lothar!

w w

Baggio my hero!

Grazie di tutto Baggio!

My Top 5:

. Years 60’ – George Best (Northern Ireland)

. Years 70’ – Johan Cruyff (Netherlands)

. Years 80’ – Lothar Matthäus (Germany)

. Years 90’ – Roberto Baggio (Italy) & Michael Laudrup (Denmark)

Grazie di tutto Baggio!

Roberto Baggio – Il mito del calcio.

Grazie di tutto Baggio!

A meu ver tecnicamente e individualmente falando Roberto Baggio é o maior jogador italiano da história.

Grazie di tutto Baggio!