Isco and Joe Cole highlight cultural differences

Real Madrid and Spain’s Isco is by today’s standards a physically ordinary player. While generously listed at 5’9’’, he has the legs of a man a full three inches shorter. The most flattering praise one might offer is that he possesses the lithe frame of a dancer, which is then only betrayed by an awkward pigeon-toed gait and tendency to comically swing his arms to his side when running.

With the ball at his feet, though, all doubt over his physical shortcomings dissolves. Gifted with pantherish quickness and an immaculately timed first step, Isco often evades his first marker to open up the pitch to pick a pass or to further foray up field, while his low center of gravity gives him surprising brawn and balance in the tackle.

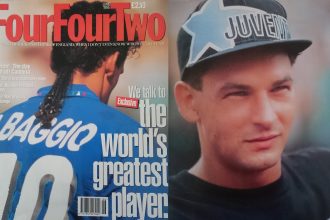

At first viewing, his style of play is reminiscent of a young Joe Cole (I’m not the first to make this analogy) who, like Isco, could play across the midfield line but was usually most comfortable operating just left of centre where it was slightly less crowded. Cole even shares a bit of Isco’s awkwardness in appearance. With a head slightly larger in proportion to his body and an ungainly high-kneed stride, Cole resembles a child’s rendering of a footballer.

Yet both diminutive schemers also stand out with their host of flicks and tricks, full of scamper and jinking industry weaving figure eights and generally wreaking havoc in the final third. While there is a frictionless and ethereal beauty to Zidane, Iniesta, and Ozil’s brand of playmaking – the kind that you could set to classical music –Isco and Cole attack with a freestyle riotousness that is absolute hip-hop.

Isco predictably gets grouped with Spain’s other crafty ballplayers, but has more in common with dribblers like Cole or even Ronaldinho than the omnicompetent, play-it-simple Xavi or the buzzing relentlessness of a David Silva. And what made Cole such a delectable prospect in his teens weren’t his similarities with the English playmaker of the past (although there were the requisite comparisons to Gascoigne) but that his streetballer flair and cockney swagger was an emblem of the “future is now” cool Britannia of the then still burgeoning Premier League.

And yet, why compare these players now? Or, better put, why even write or think about Joe Cole today? After all, there is an unavoidable past tense-ness when discussing his career, which has entered what we might call a post-Torres phase wherein we even cease to ask the question “is he back?”

Now 32, it is accepted that that Joey Cole is gone. He will probably be remembered, to paraphrase one football writer, as someone who decorated rather than dictated the most important matches – a high-end luxury player who didn’t quite earn the trust of his managers to be called to pull the strings week in and week out. Given his early promise, the relative mediocrity of his career is considered a low-grade tragedy. He was hampered by a serious knee injury while at Chelsea and had the not insignificant misfortune of playing for Jose Mourinho who, as Juan Mata is currently learning, doesn’t warm to players light on graft.

Determined to prove Mourinho and others wrong, Cole bulked up and bombed about the pitch to do his fair share of tracking back and tackling, publically proclaiming in 2010 “I have steel, I’ve got some balls”— an overwrought declaration of a player then on the margins of the national team and a far cry from the youthful scamp at West Ham who once defined bravery as “getting the ball and playing, especially when the chips are down.”

There is an urge to blame Mourinho for the devolution of Cole from expressive playmaker to a more functional all-around midfielder, but this misses the mark. While Mourinho’s football philosophy has little place for a pure number 10, neither, in many respects, does the wider environment of English football culture where an excess of guile and craft is synonymous with a deficiency in mettle and manliness.

As much as it is a cliché, the virtues and demands of refined play in England – power, pace, and passion – often end up burdening domestic players more so than their foreign counterparts who are tolerated and even celebrated for their fripperies. Traditional heroes of the British game are those real life Roy of the Rovers who through dedication (Beckham), blood (Butcher), tears (Gascoigne), and sheer gut busting crash, bang, walloping triumph (Gerrard) have left their imprint. Cole was always bucking the trend in this regard.

In truth, English football might have less of an issue with flash and dash than it does with placidity and calm. There is, after all, no more severe epithet in the English game than “languid” with perhaps the exception of “crab,” meaning a player passes the ball sideways quite a lot.

Very early in Cole’s career at West Ham the worry was he would shoulder too much responsibility and develop into a patient, pass first midfield player rather than a gung-ho attacking force, which is ironic given questions over his football intelligence in his later career. The English obsession with vertical, breakneck football might be the key reason Cole didn’t quite live up to expectations and the most notable difference between he and Isco as playmakers.

Whereas Cole was handicapped by a tendency to rush into blind corridors at full clip or overcompensate with tricks when the situation demands a more simple option, Isco has the subtly of skill to put the breaks on in an instant and pick a pass, accelerate in a different direction, or simply play the ball sideways or backwards. Rather than spinning into traffic with his first touch, Isco often chops the ball into space unoccupied by defenders both to change the angle of attack and to buy more time.

Isco has fully absorbed if not mastered the art of la pausa (the pause), a Spanish concept, meaning the ability to slow a match’s overall tempo or, in a more immediate sense, the ability to feint, jink, hesitate, or put one’s foot on the ball to buy a couple of seconds and yards to freeze and bamboozle one’s opponents –playing faster by playing slower. It is the technical capacity to create extra time and space while in possession to bring one’s team into the game. And in the hurly-burly pace of the modern game both time and space are the most treasured commodities.

The fact that so many of the finest exponents of the pause are Spanish or South American suggests that it is a learned proficiency nurtured by footballing cultures that place a premium on patience, technique, and composure on the ball. And though these qualities are often appealed to by directors of football, coaches, pundits, fans, and journalists in the English game, as Jonathan Wilson ruefully states:

“English football’s great strength is its pace and physicality, and when it fails it tends to be because those elements have become over-emphasized and a headless-chickenness has taken over.”

Cole’s career is in many ways analogous to this peculiarly English predicament insofar as his progression as a player over-emphasized the physical rather than cerebral side of the sport. Association football is an associative sport and probing and passing sideways is as much an art of the playmaker as knifing through defenses to create goal-scoring chances.

Of course it’s too soon to tell if Isco, as I’ve implied, is a more evolved version of Joe Cole, seeing, at 22, he is not yet the finished article. But the regrettably rapid twilight of one of England’s greatest ever schoolboy footballers and the recent dawn of a Spanish talent of similar but more refined skill in terms of patience and ability to control the tempo of a match, begs the question: what if Joe Cole were Spanish?

You can follow Sam Fayyaz on Twitter @FernandoPando